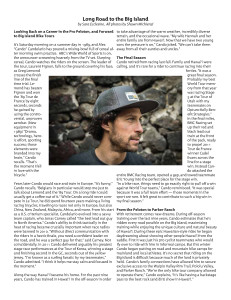

Looking Back on a Career in the Pro Peloton, and Forward to Big Island Bike Tours

It’s Saturday morning on a summer day in 1989, and Alex “Cando” Candelario has poured a mixing-bowl full of cereal after morning swim practice. ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” is on, the announcer screaming hoarsely from the TV set. Slurping cereal, Cando watches the riders on the screen. The leader of the tour, Laurent Fignon, falls to the ground covering his face, as Greg Lemond crosses the finish line of the final time trial. Lemond has beaten Fignon and won the ’89 Tour de France by eight seconds, seconds he gained by using the controversial, unproven aerobar. (New equipment in 1989) “Drama, technology, heroic effort, sporting success; those elements were branded into my brain,” Cando recalls. “That’s the moment I fell in love with the bicycle.”

Years later Cando would race and train in Europe. “It’s funny,” Cando recalls, “Belgians in particular would stop me just to talk about Lemond and the ‘89 Tour. On a long ride I could usually get a coffee out of it.” While Cando would never compete in Le Tour, he did spend fourteen years making a living racing bicycles, traveling to races not only in Europe, but also China, New Zealand, Malaysia, Africa, and more. From his start as a U.S. criterium specialist, Candelario evolved into a savvy team captain, whom Jonas Carney called “the best lead out guy in North America.” Cando’s ability to think tactically in the heat of racing became crucially important when race radios were banned in 2010. “Without direct communication with the riders in a hectic finale, you need a confident leader on the road, and he was a perfect guy for that,” said Carney. Not coincidentally, in 2011 Cando delivered arguably his greatest stage race performances at the Tour of Korea, winning a stage and finishing second in the GC, seconds out of the yellow jersey. “I’m known as a surfing fanatic by my teammates,” Cando admitted. “I think it helps me stay calm and focused in the moment.”

Along the way Hawai’i became his home. For the past nine years, Cando has trained in Hawai’i in the off-season in order to take advantage of the warm weather, incredibly diverse terrain, and the occasional wave. “My wife Hannah and her entire family are from Hawai’i. Now that we have two young sons the pressure is on,” Cando joked. “We can’t take them away from all their aunties and uncles.”

The Final Season

Cando retired from racing last fall. Family and Hawai’i were calling, and it’s rare for a rider to continue racing into their forties. “It was a great final season. Probably my best World Tour memory from that year was racing Stage 5 at the Tour of Utah with my teammates on Optum-Kelly Benefit Strategies.” In the final miles, BMC Racing set up their red and black lead out train at the front of the pack, ready to propel 2011 Tour de France winner Cadel Evans across the line for a stage win. Instead Cando attacked the entire BMC Racing team, opened a gap, and towed teammate Eric Young into the perfect place for the stage win.

“In a bike race, things need to go exactly right to pull off a win against World Tour teams,” Cando reminisced. “It was special because it was a full team effort — those moments in the sport are rare. It felt great to contribute to such a big win in my final season.”

From the Peloton to Parker Ranch

With retirement comes new dreams. During off-season training over the last nine years, Cando estimates that he’s ridden every road possible on the Big Island, maximizing training while enjoying the unique culture and natural beauty of Hawai’i. During these epic Hawaiian-style rides he began daydreaming about showing other people Hawai’i from the saddle. First it was just his pro cyclist teammates who would fly over to ride with him in informal camps. But this winter Cando began putting on road and mountain bike camps for mainland and local athletes. It’s no secret that riding on the Big Island is difficult because much of the land is privately held. Cando’s family connections have allowed him to secure exclusive access to the Waipio Valley Rim Trail, Pololu Valley, and Parker Ranch. “We’re the only bike tour company allowed to operate there,” Cando explains, “it’s like having a backstage pass to the best rock (and dirt) show in Hawai’i.”

As you would expect, mainland riders are opting for weeklong training camps with pro-level support: follow vehicles, daily bike tune-ups, and soigneur-level attention to details like rain bags and bottle hand-ups. Hawai’i locals are also encouraged to attend, and there’s a kama’aina discount.

But Big Island Bike Tours is also all about Kama’aina Mini-Camps. “We’re here for locals to do 2-3 day Mini Camps, put in some big miles, get pampered with lots of tech support, and enjoy riding new trails and new roads away from all the cars.” Right now Big Island Bike Tours is scheduling Kama’aina Mini Camps in July and August, after climbing season and before the Maui Gran Fondo, Dick Evans and the Honolulu Century. “We can help riders put in a big block of cycling miles, for either cycling or triathlon,” Cando explained. “We can go as mellow as you want, all coffee-breaks, selfie-stops and sunsets on the beach. Or if you’re a real sicko we have some ridiculous routes developed, like our Deux Volcanoes 148 mile, 21,350 feet of elevation gain point-to-point ride.” Pro-level support at the Kama’aina Mini-Camps means that once you get off the airplane, everything is taken care of. Big Island Bike Tours picks you up, puts your bike together, and provides nutrition, sag, and technical support.

The Next Big Thing

What’s coming in the future? “We’re developing a Kama’aina Speed Camp, to work on sprinting, lead outs and tactics,” Cando enthused. “It should be super fun, with lots of drills and mock-races.” Cando will also be assisting pro road Team SmartStop in the position of Assistant Director Sportif. “It will be a great way to keep my hand in and stay relevant.” Cando will travel to the Amgen Tour of California as well as hopefully the Tour of Utah, the USA Pro Challenge and Tour of Alberta. “So you know if I tell you to do something I’m telling the same thing to (pro sprinters) Shane Kline and Jure Kocjan,” joked Cando. “I want to give each rider the ‘pro experience,’ the level of support I received when I raced professionally, so they can maximize their potential as an athlete, or just thoroughly enjoy their on-bike vacation.”

For more information, email aloha@bigislandbiketours.com or visit www.bigislandbiketours.com

This article originally appeared in the May issue of Hawaii Sport Magazine.